Off the Wall showcases pieces from our permanent collection individually so you can learn a little bit more about the pieces in our museum one at a time.

*****

Kara Walker creates dreamlike narratives of nineteenth-century slavery and African-American history using the cut-paper format popular in the Victorian parlor. In her work she challenges historical memory rather than recreates history. She turns the safe and domestic silhouette style on its head to explore racial stereotypes in a lyrical and horrific blend that is part slave narrative, part Harlequin romance, and part fairy-tale illustration.

Walker’s silhouettes have elicited an uncomfortable blend of emotions in viewers since she first began showing them. She refers to the images in her work as her “inner plantation” and states, “The whole gamut of images of black people, whether by black people or not, are free rein in my mind. Each of my pieces picks and chooses willy-nilly from images that are fairly benign to fairly charged. They’re acting out whatever they’re acting out in the same plane; everybody’s reduced to the same thing. They would fail in all respects of appealing to a die-hard racist. The audience has to deal with their own prejudices or fears or desires when they look at these images. So, if anything, my work attempts to take those pickaninny images and put them up there and eradicate them.”

I’ll be a Monkey’ Uncle from 1996 is one of Walker’s earliest prints. Just a year later, in 1997, she was the youngest artist to receive a prestigious MacArthur Award.

*****

Stephen Greene was born in New York, where he studied at the National Academy of Design from 1935-1936. He continued his studies at the Art Students League, the Richmond Division of the College of William and Mary, and then at the State University of Iowa under Philip Guston. The work of Northern European Renaissance painting and Max Beckmann were also early influences.

Stephen Greene’s 1950s paintings of classic religious themes meld the precision and spirituality of the great Renaissance masters with the moody, stylized symbolism of postwar Existentialism. Of his early figurative work, Greene has stated, “I was essentially involved in a psychological state, a prison-like configuration that mirrored contemporary ideas…In painting the events of Christ’s passion, I, in the twentieth century, was not returning to another period’s aesthetic mode, but dealing with the possible meanings of hallucinations.” Greene universalized his religious themes to speak to a post-war culture of anxiety.

The paintings from Greene’s first three solo shows at Durlacher Brothers (1947, 1949, 1952) are his best-known figurative work. Of the fifteen paintings from the 1952 exhibition, nearly half are in museum collections, including the Tate Gallery, London (The Return); the Whitney Museum of American Art (The Shadow); the Nelson-Atkins Gallery, Kansas City (The Kiss of Judas); and the Art Museum, Princeton University (The Massacre of the Innocents). Greene was selected for the inclusion in the 1955 traveling exhibition organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, The New Decade: 35 American Painters and Sculptors.

*****

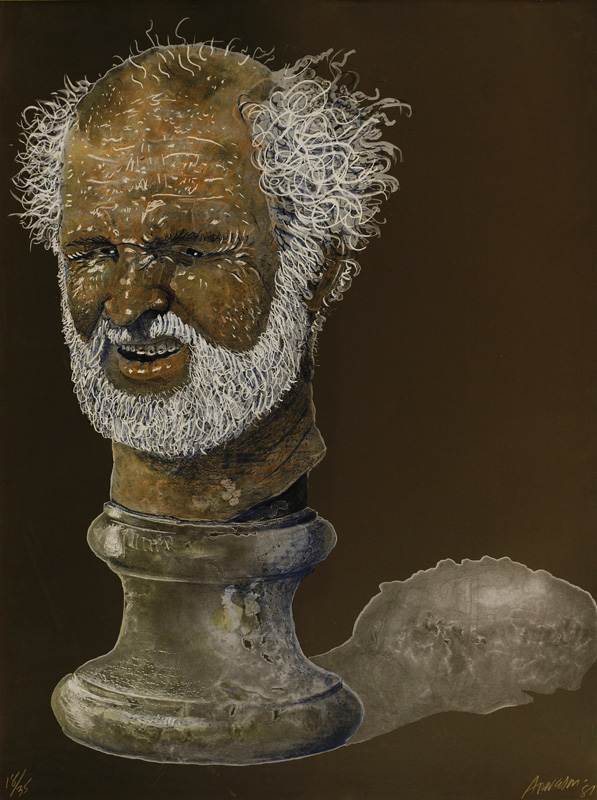

Robert Arneson was born in Benicia, CA in 1930. Between the years of 1949 to 1951 Arneson was going to the College of Marin in Kentfield, CA. Three years later in 1954 he received his BA from California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, CA. In 1958, Arneson got his MFA from Mills College in Oakland, CA.

He is well known for his work in Ceramics. He is known as using the ceramics as a vital medium for contemporary figurative sculpture. Many of his pieces of work are found at numerous museums and sites in Hawaii, Japan, California, Ohio, Australia, New York City, Illinois, and many other locations.

One thing that stands out about Robert Arneson is at the Palo Alto Art Center in Palo Alto, CA. He has over 90 ceramic Marquette’s on display. They date from 1964 to 1992 and are between 2 to 14 inches in height. It shows his more expressing nature with clay with these Marquette’s.

In 1985, Arneson was given the Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, RI. Two years later in 1987 from one coast to another in CA he was awarded again the Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts at the San Francisco Art Institute. In 1991, he was awarded the Academy-Institute Award in Art and the next year he joined the Fellowship American Craft Council. In 1992, Robert Arneson died of cancer in Benicia, CA, but will be remembered for his artwork in the world of Ceramicists.

*****

After the invention of photography in the mid-nineteenth century, artists began expanding the way they depicted a human likeness. John Sloan’s Boy with Piccolo is not a formally composed portrait; instead the artist has captured a happy moment in the life of an ordinary boy.

Sloan’s interest in social reform led him to join with other artists to form a group called The Eight. These American painters were united in opposition to the conservatism of National Academy of Design and wanted to bring painting into direct contact with life.

Later The Eight formed the nucleus of the Ashcan School, which was active through World War I. The artists of the Ashcan School rebelled against American Impressionism which was the leading style of American art at the time. In contrast to Impressionism’s emphasis on light, their works were frequently dark in tone, capturing the harsher moments of life and often portraying such subjects as prostitutes, drunks, butchered pigs, overflowing tenements, boxing matches and wrestlers.

The Ashcan artists were action painters who mirrored the ebb and flow of reality with the flux of their brushwork. Like Sloan, many were well prepared for this approach, having started their careers as newspaper illustrators. While they chronicled the lives of poor city dwellers, they were neither social critics nor reformers, but a lively bunch of provincial rebels who created America’s first true avant-garde.

*****

George Peter Alexander Healy’s father was an Irish captain in the merchant marine, and “the Celtic strain ran bright and lovable through the temperament of the son.” The eldest of five children, Healy, early left fatherless, helped to support his mother.

At sixteen years of age he began drawing, and at once was fired with the ambition to be an artist. Miss Stuart, daughter of Gilbert Stuart the American painter of George Washington, aided him in every way, loaned him a Guido’s “Ecce Homo”, which he copied in colour and sold to a country priest. At eighteen, Healy began painting portraits, and was soon very successful. In 1834, he went to Europe, leaving his mother well provided for, and remained abroad sixteen years.

Healy’s natural charm brought him many important patrons, including King Louis-Philippe of France, who commissioned Healy to paint a series of portraits of distinguished Americans for the official gallery in Versailles. After Louis-Philippe was overthrown in 1848, Healy turned again to America, settling in Chicago from 1855 to 1865. During this extraordinarily prolific decade, he produced more than five hundred portraits, including numerous official presidential images and, after the war began, those of military figures Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, George B. McClellan, and David Dixon Porter. Healy often turned to photographic images when creating his own portraits

*****

Initially trained as a painter, Barbara Morgan took up photography in the mid 1920’s after realizing its artistic potential through seeing the work of Edward Weston. From the beginning, Morgan was inclined to explore the rhythmic motions of her subjects and was drawn to modern art. In the United States, modern dance, perhaps more than any other art form, provided artists with fresh ideas to explore. Photography, too, was ripe for experimentation in the 1920’s, through manipulated images of photo-montage, light drawings using photographic processing, and other constructed forms of image-making.

In 1935, Morgan met modern dance pioneer Martha Graham; the two women found they shared a common approach and immediately decided to work together, with Morgan photographing Graham’s dance company over the next five years for an award-winning book. The shoots were preceded by conversations between the two, and hours of Morgan observing the dance works in actual theater performances. Morgan selected particular moments from the flow of peaks and repetitions throughout the dance, which to her captured its essence. Working with Graham and the dancers, she recreated these moments in the studio and based her photographs on the results. Morgan’s dance photographs rank among the classic experiments of Modern American Expressionistic photographic art. Photographic meaning for Expressionist photography extends beyond the photograph and becomes a symbol communicating personal vision and cultural values. Thus photography from an Expressionist’s point of view is not essentially a vehicle for documentation, but frequently aims at a metaphorical interpretation of its subject. Expressionists such as Morgan advocate the separation of the medium as a fine art from its functional and casual “snapshot” tradition.

*****

In a painting in the Hanford MacNider Gallery of the Museum a strong figure with a shock of dark hair pensively plays an accordion. The chair on which the man sits seems to be floating in an indefinite space, which draws the viewer more deeply into his reverie. The musician is not dressed for performance, but in work clothes, and perhaps his most striking feature is the oversized hand the artist has given him.

The painter, Todros Geller, was a Ukrainian American artist and teacher best known as a master printmaker and a leader among Chicago’s art and Jewish communities. Geller produced paintings, woodcuts, woodcarvings, and etchings. His work focused on Jewish tradition, often including moralistic themes and social commentary and the intersection of Jewish tradition with modern day Chicago. He received commissions for stained glass windows, bookplates, community centers, Yiddish and English books and was regarded as a leader in the field of synagogue and religious art.

Geller viewed art as a tool for social reform and spent a large part of his career teaching art. Many prominent Chicago artists studied drawing and painting under him, including Aaron Bohrod, whose work The Old Doll, hangs opposite The Accordion Player in the MacNider Gallery.

The Accordion Player was given to the MacNider Museum in the early 1980s by the Mason City Community School District and was produced as part of the WPA Federal Art Project.

*****

Willard Metcalf was an America artist born in Massachusetts who is generally associated with American Impressionism. After early figure-painting and illustration, he became prominent as a landscape painter.

The French Impressionists astounded the late nineteenth century art world when they took canvases and palettes out of their studios and painted directly from nature. They were particularly fascinated by a free handling of paint and the changing effect of light on their subjects. Considered revolutionary at the time, these innovations are the precursors of modernism and eventually, abstract art.

Though Haystacks may not show the dappled sunlight that characterizes the work of the Impressionists, the loose handling of paint and the outdoor scene are typical of the movement. Metcalf studied in Paris and by 1886 was painting at Monet’s Giverny. After his return to the United States in 1888, his production was erratic, but he is known for his New England landscapes.

*****

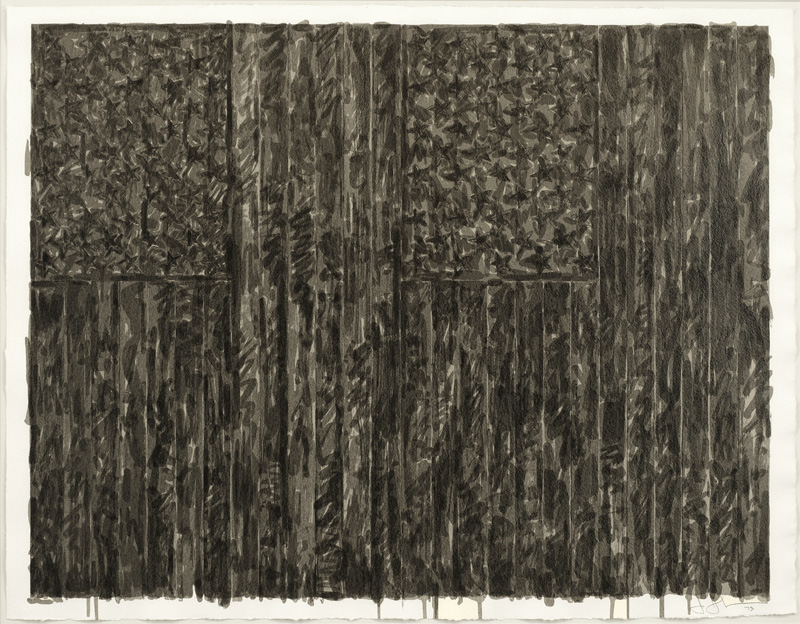

Jasper Johns was born on May 15, 1930 in Augusta, Georgia. Johns studied at the University of South Carolina from 1947 to 1948, a total of three semesters. He then moved to New York City and studied briefly at Parsons School of Design in 1949. While in New York, Johns met Robert Rauschenberg, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage. Working together they explored the contemporary art scene, and began developing their ideas on art. In 1952 and 1953, he was stationed in Sendai, Japan during the Korean War.

He is best known for his painting Flag (1954-55), which he painted after having a dream of the American flag. His work is often described as a ‘Neo-Dadaist’, as opposed to pop art, even though his subject matter often includes images and objects from popular culture. Still, many compilations on pop art include Jasper Johns as a pop artist because of his artistic use of classical iconography.

Most of Johns work can be found mostly on the east coast of the United States. To name a few of the places, Museum of Modern Art in New York, the New York State Theater, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and many others.

In 1998, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York paid more than $20 million for Johns’ White Flag. In 2006, private collectors Anne and Kenneth Griffin (founder of the Chicago-based hedge fund Citadel Investment Group) bought Johns’ False Start for $80 million. Johns currently lives in Sharon, Connecticut.

*****

Alfred Thompson Bricher was an American painter who specialized in marine subjects, with particular emphasis on subjects from Maine, the Bay of Fundy, and the Maritime provinces of Canada. Largely self-taught, Alfred Thompson Bricher studied in his leisure hours at the Lowell Institute in Boston and also attended an academy in Newburyport, MA. Bricher was a businessman in Boston from 1851 to 1858 before he became a professional artist. Bricher was often associated with the group of painters known as “the Hudson River School”. He espoused a conservative and realistic approach to landscapes, while his interests lay not only in the play of light, water, and air, but in a sense of luminosity and spirituality in nature.

Oddly, Bricher continued painting peaceful scenes of nature even at the height of the horrors of the Civil War, a war in which he younger brother was killed. His perseverance in this style underscores his belief in the eternal forgiveness of Nature and the truism that whatever the acts of man, Nature is the more powerful force.

During the later part of his career, Bricher witnessed the advent of modernism, a movement that seemed to make many of his artistic concerns obsolete – but which, in another sense, owed a debt to the discipline and realism in works by Bricher and other Hudson River painters. He is still considered one of the best maritime painters of the late nineteenth century.

*****

John Bernard Flannagan was born in 1895 in Fargo, North Dakota. His newspaperman father died when John was five, forcing his destitute mother to place him and his sister in an orphanage. Unrelenting poverty plagued him the rest of his life. He got into carving as a youth and moved to Minneapolis in 1914 to study painting at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. During World War I he served in the Merchant Marines until 1922 and then took up residence in New York to resume his study of painting.

Around 1926, Arthur B. Davies, one of the prime movers and shakers in early 20th century American art circles and a key figure in the implementation of the famous “Armory Show,” discovered Flannagan in a state of near-starvation. Davies took the still young artist to one of his farms and nurtured his health and spirit for about a year. Flannagan was still pursuing his study of painting but at the suggestion of Davies in 1927, he tried his hand at wood sculpture, starting on a track that he would follow for the rest of his career. He discovered stone as a medium in 1928 and it became his favorite.

He has been critically acclaimed as one of the best of his generation of artists employing what became known as the “direct carving” approach to making sculpture. Flannagan’s own sculpture did not follow the academic traditions, which preceded and still dominated during his time. He worked with fieldstones instead of quarried ones; a choice affected more at first by economics, but one that proved right for his art.

Personality was instilled into the stones touched by his tools and his imagination, capturing and reflecting many moods and mysteries of life. In 1929, in a letter to Carl Zigrosser, John Flannagan said, “My aim is to produce a sculpture…with such ease, freedom and simplicity that it hardly feels carved, but rather to have always been that way.”

*****